Theological Prospects for Mideast Peace

An experiment in Wiki Web Diplomacy

by Scooper

28 January - 10 February 2005

"Holding rallies and having marches," he said, between blowing Home on the Range on his harmonica, "you're playing their game .... There's only one thing to do. ... And that's everybody just look at it look at the war, and turn your back and say... 'f--k it.' " — Ken Kesey protesting the militancy of peace protesters at the Vietnam Day rally, Berkeley, California, 1965

|

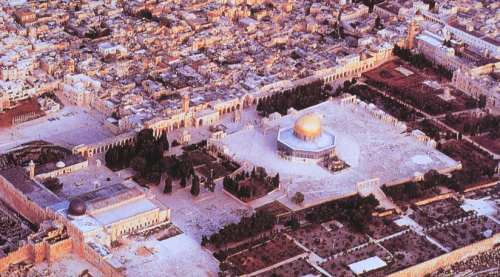

| The Temple Mount (al Haram al Sharif) after a rare snowfall. The Dome of the rock is visible near the center of the image, and the al Aqsa mosque is near the lower left. |

Introduction: Why Theology?

The history of conflict in the Middle East probably dates back to the beginnings of human civilization, due to its strategic location as a crossroads between lands controlled by more powerful neighboring societies. However, the period of recent conflict has its roots in the declaration of the nation-state of Israel on May 14, 1948.

This development is remarkable in that, for the Jewish people, it ended some 2000 years of living in diaspora, without a nation-state of their own to give themselves cohesion, much less protection. Without some powerful internal source of cohesion, the fate of most dispersed peoples has been assimilation and disappearance. Whether one believes the source of Jewish cohesion to be a religiously motivated set of ritual and social practices, or the will of the Creator of the Universe, the remarkable survival of the Jewish people to found a nation-state on approximately the same land from which their ancestors were evicted by the Roman Empire can be attributed to a single word — God. That is to say, the ultimate source of Jewish identity and of Jewish claim to the Land of Israel is theological.

In particular, Jews claim the Temple Mount (al-Haram al Sharif to Muslims) as the world's holiest site, since that is where the First and Second Temples to God once stood. More extreme Jews believe that the Temple must be rebuilt before the Messiah comes to establish a holy Kingdom on earth.

Similarly, the people who were displaced by the founding of modern Israel identify themselves in a theologically as Muslims, "submitters" to the will of God. They claim the land, because in A.D. 620 (B. H. 2 of the Islamic Calendar) Islam's Founder, the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) experienced the Lialat al-Miraj (Night Journey) in which he was transported to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, and ascended to Heaven. (At the time, the Temple Mount was the Qibla, the place toward which Muslims faced in prayer, until it was changed to the Kaaba in Mecca four years later.) According to Muslim teaching, this event and its former status as Qibla, render the entire top of the Temple Mount holy, and therefore a mosque. To commemorate this, the Umayyad Khalif, 'Abdul Malik ibn Marwan, amd his son, al-Walid, built the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa mosques on top of the Temple Mount during A.D 685-705. Thus the source of Muslim identity and claim to the same land that the Jews claim, and especially to its holiest site, is also theological.

We also note that this region has been claimed by Christians to the extent that they fought the Crusades for 200 years (A.D. 1095—1291) in an attempt to wrest control of the region from Muslims. The Crusaders wanted to assure Chistians access to Golgotha (where Jesus was crucified), to the Holy Sepulchre (where Jesus was buried), to Bethlehem (where Jesus was born), to Nazareth (where Jesus grew up), and to the Temple Mount (site of the Second Jewish Temple, where Jesus preached). Christians consider these sites to be the holiest on earth. Therefore we also note a theological connection of Christianity to the Middle East. Indeed, a strong component of the Western support for the continued existence of the nation-state of Israel is motivated by Christian religious sentiment (possibly in expiation of the historical guilt accumulated by Christians for persecuting Jews, culminating in the Holocaust or Shoah of the 1930s and 40s in Europe). In addition, some more Fundamentalist Christians support Israel in the belief that the Temple must be rebuilt before the Second Coming of Christ to redeem the world.

Thus there is a strong theological component to the claims and counter-claims fueling modern conflict in the Middle East. That this conflict is sociological, ethnic, and tribal is not denied here. But it is clear that without convincing theological justifications, sympathy for the extremists of all parties will not abate sufficiently to enable a peaceful resolution to the modern conflict.

It is equally clear that such theological justification must take the faith-claims of all parties at face value, and seek to fulfill the prophetic traditions that all parties espouse. It is therefore the aim of this article to explore whether theological justifications for peace can be discovered in the traditions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. To put it in blunt theological language, under what circumstances, if any, will God, the one God of Jews, Christians, and Muslims, permit peace in the Middle East?

Exclusive and Inclusive Claims

Typical exclusive claims include the insistence of some radical Jewish and Christian groups that all existing architecture be removed from the Temple Mount to make way for rebuilding the original Temple of Solomon as described in the Hebrew Bible, and the insistence by some radical Muslim groups that only Muslims be allowed on or near the Haram al-Sharif. Indeed, the Waqf that currently has jurisdiction over the top of the Mount seems to be intent on erasing all archaeological traces of Jewish presence on the site, in order to deny the legitimacy of Jewish claims to the site.

Inclusive claims are as yet unrealized, but could stem from re-examination of the scriptures of the three religions for whom the site is holy. Such claims could be based, for instance on the Qur'an, sura 2, verse 62 and sura 5, verse 69:

Surely, those who believe, the Jews, the Christians, the converts; all those who believe in God and in the Hereafter, and do righteousness, will receive their recompense from their Lord; they have nothing to fear, nor will they grieve.

One could assert that this statement must have some importance, because it occurs twice in the Qur'an in widely separated contexts. It implies that Muslims must assert that they worship the same God as do Jews and Christians. Thus,Muslims might assert the mosques of al-Haram al-Sharif are places of worship for Jews and Christians as well as Muslims, and that therefore the Temple of Solomon need not be rebuilt.

Christians could look to prophetic statements in the New Testament, such as Revelation, Chapter 15, verse 4:

Who shall not fear thee, O Lord, and glorify thy name? for thou only art holy: for all nations shall come and worship before thee; for thy judgments are made manifest.

One could assert that this prophecy is being fulfilled by Muslims, Jews, and Christians all seeking to worship at the Temple Mount.

Finally, Jews and Christians can both look to Malachi, chapter 1, verse 11

For from the rising of the sun even unto the going down of the same my name shall be great among the Gentiles; and in every place incense shall be offered unto my name, and a pure offering: for my name shall be great among the heathen, saith the LORD of hosts.

One could assert again, that the response of Muslims and Christians to worship God represents an unexpected fulfillment of this prophecy.

Thus, there may indeed be grounds for re-examining old interpretations of scriptures to search for conditions in which the God of Abraham, the progenitor prophet of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam could permit his children to make peace with one another, and to consider the pre-conditions for their eschatological hopes to be satisfied.

This article is necessarily unfinished, because to be of value, it must be the work of many, not just one. I plan to post it to Wikipedia, and to let whosoever will edit it and expand upon it. May it spawn waves of constructive thought among the clergy, the rabbis, the ulema, and their followers in the Body of Christ, all Israel, and the Umma. See how it is changing by clicking here.

Er, don't bother. It's gone without a trace.